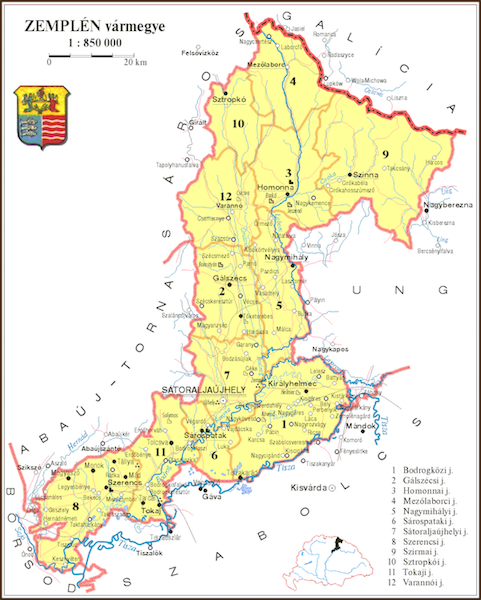

Isaac Schwartz's family sojouned from Austria-Hungary (Zemplen, Satoraljaujhely), to Philadelphia, to Chicago, to Mobile, to New York, and finally to Columbus. Isaac entered the US in Philadelphia from Austria-Hungary. his wife, Rose Goldberger Schwartz, had relatives in Chicago so they moved there fairly soon after arriving.

Isaac started a business making or selling some kind of Xmas cake in a woven basket with a relative of his wife, named Willie Goldberger, in Mobile. The material for the baskets came from Mobile and apparently it was easier to make the whole package in Mobile, so the family moved to Mobile after a few years.

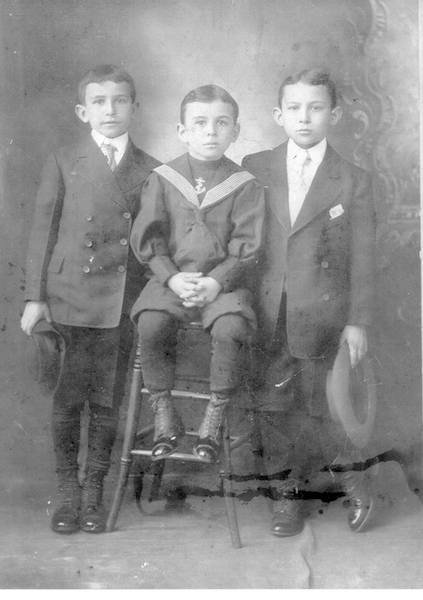

While in Mobile, Isaac became the president of a fledgling synagogue, Ahavas Chesed, and led it to its first major purchases, a meeting place and a cemetery. Their children William (Willie), Harry, Helen, and Sam ("Babe") were raised there.

After high school graduation, Willie applied for college. He was accepted at Alabama University, the Naval Academy, and City College of New York. The Naval Academy was nixed by his parents, and his mother had had enough of Alabama. So Willie went off to New York, where he lived with a relative. The relative owned a tavern in Hell's Kitchen where Willie worked at night. He was so disgusted by the "clientele" that he would never let a drop of "spirits" or wine pass his lips for the rest of his life!

This was no passing fancy. Aunt Lalie remembers that her father, Willie, was vehement about all booze. When his father passed away, Willie, as the oldest, had the role of leading the family Seder. He refused wine—and even grape juice—because it resembled wine. Lalie said that Grandma was very resourceful and figured that tomatoes were also a fruit of the vine. So she squeezed tomatoes and they used tomato juice for their four cups.

While Willie was still in school in NY, the family moved there to join him. They bought a little grocery store or some other kind of food specialty shop and stayed in NY until Willie finished college. A family story has it that the education in Alabama was so bad that he had to take remedial courses as pre-requisites for admittance. One of the courses he took was U.S. History: that was the first time he learned that the South lost the Civil War! When Willie's grandson David asked him what he was taught about the war, he said the students were always of the belief that there was no winner in the war and that it ended in a stalemate or it was undecided. That little twist of history may be the cause for the term "The South never stopped fighting the Civil War.")

In New York, Willie's younger sister Helen was thrust into high school with her very poor Alabama education. She was ridiculed for her deep southern accent. She was befriended and protected by a tough classmate who loved her accent and wanted to learn it. The girl's name was Ethel Zimmerman— she went on to become Broadway's Ethel Merman!

Willie's brother Harry met Regina (Ruth) Straus at a Jewish singles dance and asked her out. Ruth said her mother wouldn't let her go out alone with a boy they didn't know, so Harry had Willie go out with Ruth's best friend, and they double-dated on some kind of a boat cruise. Apparently the problem was their being Hungarians ("hunkies") and not German ("yekkes"), like her family. Somehow the attraction shifted to Ruth and Willie.

Willie arranged to have Ruth become a tutor for Helen to help her get through 12th grade and pass the NY Board of Regents Exam. Ruth always said that she spent two years in 12th grade: once on her own, and once with Helen. Ruth had a teacher's degree and was employed by the New York Public Schools. Willie and Ruth got married. Teachers at that time were not allowed to be married, so she had to hide being married. Soon she had to hide being pregnant, too! Ruth taught in a school with mostly Italian immigrant children, who had a reputation of being tough ones. Her no-nonsense attitude must have stood her in good stead.

About this time, Isaac read about a bakery for sale in Detroit. He and Willie took a train to go visit and buy that bakery. Isaac, who was known for being a bit on the restless side (today he would have likely been labeled with some combination of A's, H's, and D's), decided to get out of the train in Columbus. Family legend has it that he sniffed the air, and opined that they would surely be able to set up a successful bakery there. He looked around Columbus and thought it looked nice. He and Willie took a cab to the Jewish neighborhood and approached the owner of a Jewish bakery (Morris Luper), made an offer, and bought it on the spot. That's how the family ended up moving to Columbus. Willie's daughter Lalie was a few months old back in 1922 when the family moved. Family relative Milton Straus came along, too.

The Schwartz family bought the bakery from the Lupers, but there may have been a loophole in the non-compete. With Schwartz Bakery showing signs of success, Morris Luper's son, Abe, re-opened a bakery just 4 doors down the street! Isaac Schwartz had to buy that one out too (with a stronger non-compete)! Some years later, Helen Schwartz was to marry Sam Valcov, who was part of the Luper family. One can only imagine that dramatic scene!

Originally, the bakery put men in wagons (later trucks) to assigned neighborhoods and they developed sales routes. The salesmen/truck drivers would buy their assortment of baked goods and go out and re-sell it to homes on their route. At the end of the day, they would return the unsold items. Lalie remembers long lines outside of their back door during the depression when she would stand at the door and sell half loaves of day-old bread for a penny. At the end of the line were poor Jews who would get their bread for free after the rest had left.

In those days of the depression, not everyone could afford the bread, which was 10 cents for a pound loaf at the time. The "day-old" and free bread was a lifeline for some. As the saying of my youth repeated,

“More bread left by the back door than ever went out the front.”